Just over 3 years ago FreeAgent was running with 4 front-end frameworks, Stimulus, React with Redux, Rails UJS and jQuery and we were about to start adding Turbo to the stack. Running all these different frameworks was not sustainable and we chose to reduce our number of dependencies and first up was jQuery. We called this our legendary jQuery code, code that had helped us grow a business and provide value to our customers. Sometimes legends need to retire and just a few weeks ago we finally removed jQuery from our stack. In this post I’ll go over the rationale behind why we spent all that time (and money) removing jQuery, how we went about it and some of what we learned along the way.

Did we really need to remove jQuery?

Before we started on the journey of removing jQuery we spent some time trying to answer the question of whether or not removing jQuery was something we really needed to do. Removing a framework from the code base that had provided value for nearly 15 years is not a decision to take lightly for any engineering organisation. Doing so is going to cost money and divert effort that could be used to deliver customer value and divert that to a long running maintenance project. To answer that question at FreeAgent we thought about how jQuery was affecting our security, reliability and ability to deliver value to the customer with an engineering organisation that knew less and less about jQuery.

In FreeAgent we were running an old version of jQuery that we had manually patched to fix various vulnerabilities over time and was continually picked up as a risk in pentest and security audits. We discussed trying to upgrade jQuery to get back to the main line but this wasn’t going to be a simple upgrade. We used many deprecated and removed jQuery APIs, like livequery, and the code that used that would have needed to be rebuilt and tested before we could move to the next version, a process that would need repeating several times to get to the latest version of jQuery. This was a possibility but didn’t align with our strategy. The decision had already been made to move towards using Hotwire as our front-end framework of choice, with the team writing all new code with Hotwire and where possible replace jQuery with Hotwire. Given how much of the code used these older deprecated jQuery APIs, trying to upgrade jQuery would have been a similar effort to replacing the code with Hotwire but without any of the benefits.

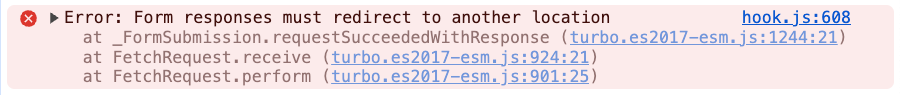

We had to consider how running these multiple frameworks was affecting our engineers and their ability to ship features. We could see with our initial work of writing new features with StimulusJS that jQuery was causing issues for our engineers. Using this combination of frameworks was creating unexpected bugs in the code. For example we were seeing events that were triggered by jQuery were not always picked up by Stimulus depending on how the event was being triggered, or when Stimulus would update the DOM jQuery code that used older APIs was not running code that was required to update the view correctly. These issues forced our engineers to think more about how the 2 frameworks interacted instead of concentrating on building rich UI for our users which is what we want engineers doing.

This cognitive overload also extended to our test suite. Our new Stimulus code was being tested with Jest whereas the old jQuery code was being tested with Karma and Jasmine. Although these were somewhat similar they still represented a need to think of 2 different frameworks when working on code, remembering how to run each test in the different frameworks. We also had to maintain all the dependencies for both sets of tests. All this combined just made our engineers’ lives harder than it needed to be.

So in the end we chose to remove jQuery and re-write all the existing jQuery code to use Stimulus and Turbo. This mission would be led by one of our platform teams who expected to do most of the heavy lifting so that our product teams would not need to stop what they were doing.

First steps on of our mission

Before we started, we came up with some questions we needed to answer quickly about how we were going to remove jQuery. As Turbo at the time was brand new to the scene we wanted to validate that Hotwire was the right choice to replace jQuery with. We needed to do this in an area of the app that had the right amount of complexity so we could explore and experiment with Hotwire to make sure it was up to the task. We also wanted to figure out how best the team could work with the product teams, understand how best to communicate between teams about what we were doing, the level of support both sides would need and build confidence that a single team could successfully work to replace the old code. We knew early that unless we could build that confidence it was going to be an even harder challenge to remove all the jQuery.

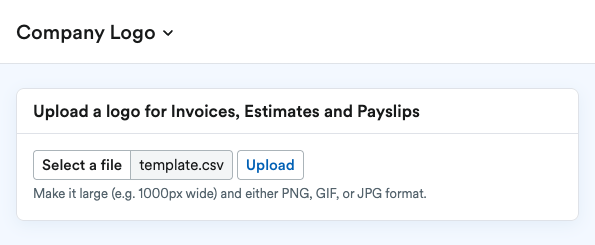

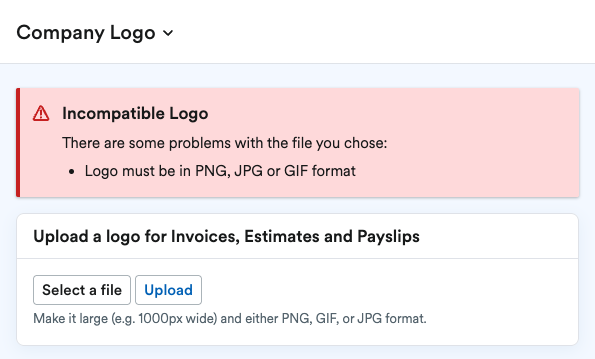

We chose to start in an area of the app that didn’t have any feature improvements planned at the time but contained many of the UI patterns that we used within the rest of the app. Choosing a feature that was a lower priority at the time for the product team allowed us time to experiment with Hotwire free from having to coordinate work with the product team. This gave us the space to learn what we could do with Hotwire and once the code was shipped into production we could check that the framework didn’t compromise on the user experience that previously existed.

When we started working to remove jQuery we had a set of practices on how we would interact with product teams that we felt would work, but these practices did not last for the entirety of the mission. Over time these practices changed and evolved. These changes happened in part because we became more confident in removing jQuery and as product teams became more confident that we were delivering improvements on code. As the mission progressed, we became more flexible in our ways of working, fitting in with existing practices of the teams we were working with to get changes reviewed and tested, ensuring we were both delivering code that didn’t break existing functionality and also to share knowledge on the changes that were being made. The one practice that didn’t change between teams was the “3 month guarantee” on anything the team changed. The guarantee was there so that teams would not feel left alone with code they may not have written which was now failing and to make sure that the team took ownership over the changes.

Protecting the mission

Replacing jQuery was never going to happen overnight so the team needed to tell a story of how the mission was progressing and ensure that we were moving in the right direction. We discussed lots of fun and interesting ways to track our usage of jQuery. We explored ideas like tracking calls to jQuery or adding tracking to each method that would allow us to see if a method had become redundant. In the end we chose to keep it really simple and used the number of lines of legendary javascript code as our KPI. This was not a precise measure of progress, it lacked precision around when code may have been replaced but was still in the app along with included comments but it was good enough for our purpose to show the progress we were making toward the end goal to execs and stakeholders.

The KPI was great to show progress but we needed to make sure that teams were not adding or modifying the jQuery codebase with a higher fidelity than the once a month recording of the KPI, we needed to monitor for changes to legendary code and did this by adding the team as owner of all the legendary code. Although we could have used notifications to put a stop to changes to the legendary code, we instead used the notifications as an opportunity to talk to teams about the legendary code. We tried to understand why they were changing the code and if there was an opportunity for the team to help replace what was there rather than just updating old code. In some cases it was unavoidable to change the legendary code, bug fixes were still required and changes were needed to make it easier to transition to newer Hotwire base implementations, but these conversations allowed the team to speak to the product team about their challenges of replacing legendary code. It offered opportunities to pair with product engineers to remove legendary code and allowed us to share knowledge and experiences replacing the legendary code with Hotwire.

Ensuring we could communicate our progress through simple KPIs and monitoring the changes to the legendary code made sure we were continuously pushing forward with the mission. The opportunities that arose from conversations around changes to legendary code also allowed us to reinforce the mission across all of engineering.

It wasn’t always about jQuery Zero

A big deliverable like removing jQuery needs focus but it is more than just churning through lines of legendary code until we reach the end. We needed to keep space for helping and inviting others to work with us on the mission. As mentioned above we use the notification of changes to legendary code as an opportunity to help others but that wasn’t all we did. We did internal talks about the new tooling and ways for working with Hotwire, we documented ways for solving common problems within the application, and we ran workshops with engineers to train them on ways of working with the tooling. As the education and knowledge sharing was important to us and important to the mission succeeding, we tracked the amount of knowledge sharing against a KPI. We used this KPI as a lever to give us the space to put down the churn of removing jQuery and talk to other engineers to spread the vision of an app without jQuery and how we could work together to achieve it.

There was more the team could do than just removing and talking about removing jQuery. With the knowledge we were building through removing legendary jQuery and seeing patterns we saw emerging from the changes, we tried to make it easier for teams to use Hotwire by creating tooling and libraries to do common functions. We wrote testing tooling to make it easier to write tests for Stimulus controllers by removing lots of boilerplate code and giving a consistent structure to the tests. As FreeAgent is a very form-heavy app we looked at ways to make creating forms with dynamic content easier to build by making a component that leveraged morphing and server side rendering to apply the required changes to the forms. Writing these tools gave an outlet for the team to be creative with code and solve problems for our customers, the product engineers.

Just continually replacing legendary code can be a tough ask for any team without some other creative outlets. We channelled that creative energy into writing, presenting and building tooling to help others deliver features all while still removing jQuery.

Mission Achieved

The journey to jQuery zero was a long one, in all it took about 3 years to complete. In doing so we have been able to remove a large dependency of our application removing complexity and making the product more secure and reliable. A mission like this cannot be achieved alone and needs to include all the stakeholders on the journey to end on a successful delivery. If you are considering doing something similar be very clear in why you want to remove the legendary code, find somewhere in the your application where you can experiment without getting in the way of others, build confidence with stakeholders and make space to help and communicate with them, finally find ways to be creative to bring variety to the work.